Healing in Light Filled Rooms

Every week, in a light-filled room, I share experience, strength, and hope with women of all ages and backgrounds.

HOW TO DRINK BEER

1. The first bottle brings a slight sense of lightness. You have an intense desire for that second bottle.

2. The second bottle brings a warning signal. I feel fine, very fine, and have the unusual ability to talk about anything with anyone. I realize I should quit now, but my goal is twelve.

3. Bottles three, four, five, six and seven have no place in my memory. They are a mixture of music, cigarettes, and swimming. At this time, I have the urge to run out into the sea, but my friends pull me back. I pass out for twelve hours, then wake up with the ‘whirlies,’ and we all know what happens then.

4. Then comes the hangover.

5. Then comes crying.

6. Then comes laughter because I can pretend nothing happened.

7. Where’s some more beer?

In tenth grade, I wrote “How to Drink Beer” for the standard English class process essay assignment. The teacher often arrived at our third-period class reeking of cigarettes and alcohol. I wanted to tweak her and show off for my friends.

Rediscovering the essay now, I wonder if anyone could have helped me escape my own downward spiral. I could so easily have become that tragic statistic: sixteen-year-old drowns after prom. Overdoses on alcohol and drugs. That child who breaks her family’s heart.

Yet when the school counselor gathered a few students together to “talk about our feelings,” we remained silent. At home, my parents practiced the Skinnerian technique, subject of my father’s master’s degree thesis. Ignore bad behavior and reward the good.

The problem in my case was that there was little to reward. My parents, five kids in tow, presented our Family Council meeting to their college education class. I argued that stealing and crashing my father’s truck with a gang of friends should be overlooked. My siblings all voted for exoneration.

The professor took my parents aside. “That one’s headed for trouble,” he said.

My parents’ best friend attempted his own intervention. I was indeed headed for trouble. What I needed was more partying. “Spend the summer having fun,” he told me. “Get it out of your system.”

I’d never tried drugs, but he suggested he could provide some.

I started drinking at fourteen at a slumber party. Half a dozen girls swallowed booze from Mason jars they’d filled from their parents’ stash. I loved the feeling of being crazy drunk. I immediately went into my first blackout, when one keeps on doing stuff, but memory stops.

The following day, the girls reported in awe that I told our head cheerleader I hated her, and she was a bitch.

I made Cyndee cry!

I couldn’t wait until the next time. I watered down my parents’ meagre bottles of wine, stole from families I babysat for, and at wild forest parties, drank to oblivion, sometimes waking up half-clothed with no idea how I got there.

After years of being an outsider, I was finally “in.” Oblivion helped me endure the next few years. I would happily have blacked out that entire time. I need to add that during my drinking years, I was always on the honor roll. Don’t be fooled by the straight-A student. She might be the saddest of all.

Not long after I wrote that essay, I took my parents’ friend’s suggestion to party even more. I lasted one week. Rather than join my family at our Pulali cabin, I stayed in the city with a friend. Tucked into a sleeping bag in her backyard, I had a revelation. I was living the wrong life. I didn’t want to party. I missed what I’d given up when I took that first drink to join the in-crowd. I missed painting and writing and reading and music.

I missed my family.

The solution? Drinking, of course. At ten in the morning, after my friend left for her summer job, I started in on her father’s booze collection. Then I hit the streets, where I collected a gang of kids. We stole a car and crashed it. We ran into some guys in their twenties who somehow separated two of us girls from the others. I told them my parents’ house was empty for the summer.

The men provided sufficient hallucinogens that, combined with the alcohol I’d been drinking all day, were “enough to kill three grown men,” the physicians later told my parents.

It was only fortuity that my parents had driven to the city for a play, and my father needed to pick up something to wear. They found my body on the living room floor. They spent the night watching their child writhe in a straitjacket in the public health hospital.

When they drove me back to Pulali, I thought I’d been there all along. I was still hallucinating, but the high was wearing off. I set off through the forest to my parents’ best friend’s cabin, drank all his booze, then again decided I should die.

I arranged my body on Highway 101 and waited for a logging truck to pass.

Years later, I shared this with a group of loggers at a recovery support group in Sequim. One of them approached me, weeping, after the meeting. “I could have been driving that truck,” he said.

When I was sixteen, though, nobody suggested I had a drinking problem. I had a moral problem. I was bad. In my journal, I wrote “I am the embodiment of evil.” My friends said I should never return to school because I’d ruined their summer and “got those guys in trouble with the police.”

I spent my summer reading Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses from my parents’ bookshelf.

I’d flown near the sun, but somehow survived.

In the fall, I didn’t have to face my old crowd after all, because I won a dean’s fellowship to the Annie Wright School. In the anonymity of a plaid uniform and the thrill of academic rigor, I was free to use my mind. The following summer, I won another fellowship to the Institute of Nations near Berkeley. A small group of teenagers from all over the U.S. studied Africa and South America with black and brown scholars and leaders. Annie Wright bought me time, and the Institute provided role models and peers.

With more perilous crashes and overdoses along the way, it wasn’t long before I found a path to recovery. On July first (Canada Day!) I celebrate forty-two years drug and alcohol free. Every week, in a light-filled room, I share experience, strength, and hope with women of all ages and backgrounds. I am grateful to be alive.

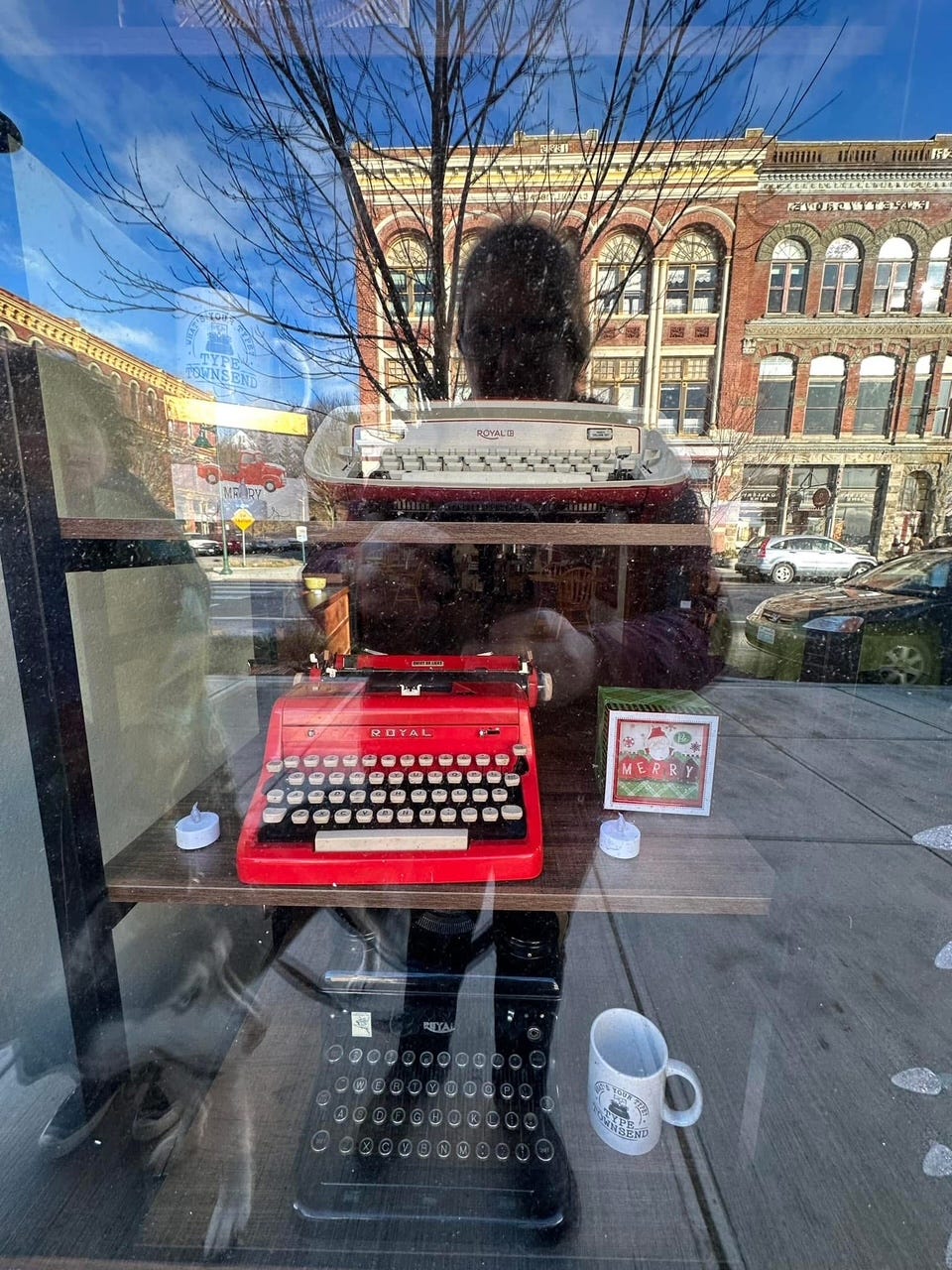

Holistic veterinarian, friend, and neighbor Dr. Anna Maria Wolf takes many of her photographs while hiking with her dog, riding her horse in the Olympic Peninsula wilderness, or in charming seaside Port Townsend, my birthplace.

Beautiful. Thank you.